Photo: AP

National Guard Law: risky confusions

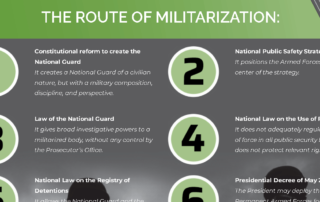

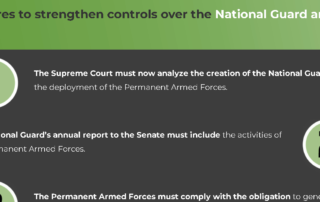

In this article we will address three main concerns that the National Guard Law raises from a human rights perspective. This Law was published in the Official Federal Gazette on May 27, 2019; the previous leadership of the national ombudsman’s office (CNDH) considered several of its articles unconstitutional or against international law and filed an action of unconstitutionality that the SCJN has not resolved to date.

The first concern is related to Articles 9 and 100 of the law. These authorize the National Guard to carry out investigations for the “prevention of crimes;” administrative verification tasks; gather information to generate “preventive intelligence;” require documents from authorities and individuals; request information, with the prior authorization of a judge, from concessionaires and providers of telecommunications services; obtain, analyze and process information to prevent crimes; and to request, after judicial control, communications interventions regarding crimes listed in article 103 of the same law.

Although it is constitutionally valid that the investigation of crimes is one of the functions of public safety, the way in which this is materialized in the law is not compatible with the constitutional precept that indicates that the police will act “under the leadership and command” of Prosecutors.

The National Guard, a militarized body without controls, was authorized to deploy these powers without being under the leadership of the Prosecutor’s Office, confusing the areas of prevention and investigation, which the Constitution clearly distinguishes in article 21.

In addition, this law contravenes the rulings of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the cases of Campesinos Ecologistas vs. México and Alvarado vs. México, which establish that conferring powers on a militarized body with respect to the investigation of crimes is not compatible with the American Convention on Human Rights.

Second, Article 9 grants powers to the National Guard in immigration matters, which implies military participation at least in the first five years. According to international human rights standards, there is an emerging consensus regarding the need to limit the intervention of the Armed Forces in migratory containment tasks, considering the special vulnerability of the migrant population, as has been referred to by the IACHR[1]—with a special focus on Mexico[2]and by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants[3]and the UN Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.[4]

The last concern has to do with the fact that Article 60 of the law considers the crimes of torture, cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment and forced disappearance as non-serious offenses. This contravenes international obligations that Mexico has signed, such as the Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture and the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons, which state that States must ensure that these acts are punished with penalties commensurate with the seriousness of the conduct. Although the processes referred to in the National Guard Law are administrative and complementary to an eventual criminal process, they should also be consistent with the seriousness of the conduct.