Photo: Cuartoscuro

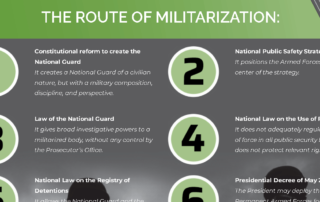

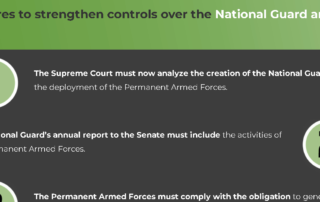

A weakened National Law on the Registry of Detentions.

The National Law on the Registry of Detentions, published in the Official Federal Gazette on May 27, 2019, raises a particular concern: it brings uncertainty to the obligation of the elements of the Armed Forces to carry out the Registry. The previous leadership of the CNDH considered several of the law’s articles unconstitutional or unconventional and filed an action for unconstitutionality that the SCJN has not resolved to this date.

The uncertainty generated by the law comes from reading Articles 19 and Fifth Transitory together. Article 19 exempts the authorities that carry out public safety support functions from recording the arrests they make in the Registry, opening the door for the Army and Navy to excuse themselves from complying with it. Then, the Fifth Transitory expressly refers that the Permanent Armed Forces, during the five years in which it will intervene in public safety, will be governed under the provisions of this law.

From a constitutional perspective, this design undermines legal security by generating uncertainty and, from an international law perspective, moves away from the obligations of the Mexican State.

The obligation to create a registry of arrests was reinforced in the judgment of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the case of Campesinos Ecologistas and does not foresee that the Armed Forces are exempted from carrying it out. On the contrary, being a case in which the violations were committed by military personnel, it should be understood that this measure was proposed as a guarantee for non-repetition capable of increasing the control over the Armed Forces.

Therefore, it would be incompatible for the Armed Forces to be exempted in a secondary law from carrying out the Registry. Even if we accept that the Fifth Transitory cancels the exception generated by Article 19, it would open the door for the Armed Forces to be exempted from carrying out the Registry once the five-year period has concluded, without any justification.

Furthermore, the National Law on the Registry of Detentions does not fully comply with the other characteristics of the Registry ordered by the Inter-American Court. For example, it does not meet the access to information requirement for cases of detainees charged with organized crime. It will be possible to know where a person accused of a common crime is detained, but for those accused of organized crime, only the date of the arrest and if the person is detained will be available.[1] This omission has an important impact on the protection of personal integrity, since these people run a high risk of suffering torture or mistreatment[2] –the incidence of which has been related, among other factors, to the participation of federal forces in operations to combat organized crime.[3]

Furthermore, it is worrisome that the law contemplates the possibility of justifying the failure to immediately register the detention “when there is a delay or it is impossible to generate the registration” (art. 21, para. 3).

Finally, the law brought the loss of a relevant element: The General Law of the National Public Safety System was modified to eliminate the requirement to take color photographs of detainees front and profile as well as a panoramic photograph of the place of detention,[4] further weakening the protection for detained persons. Since, if properly implemented, this requirement could contribute to inhibiting the practice of torture.

Photo: Reuters