EDITORIAL | A presidential term of militarization

The militarization of public safety policy, a process that has been ongoing for several decades and intensified after the six-year term of the Calderón administration, has brought countless victims of serious human rights violations. Although the arrival of Andrés Manuel López Obrador to the presidency of Mexico raised expectations about a change of course, what has happened in these three years contradicts that hope.

The legal scaffolding erected by the current Federal Government goes far beyond what the Armed Forces themselves had demanded in previous terms. The acceptance of the Supreme Court (SCJN) of military intervention in public security tasks when deciding Unconstitutionality Action 1/96 during the presidency of Zedillo, the appointment of an active military officer to the position of Attorney General and the de facto amnesty to the Army for the crimes of the Dirty War during the Fox administration, the proposal to reform the National Security Law in the administration of Calderón, and the Interior Security Law in the Peña government are the antecedents of a militarization process that has deepened.

The announcement of the creation of the National Guard was the first step. Although on paper the National Guard was established as a civilian entity, a series of laws and its own configuration caused this characteristic to be diluted to the point that the Guard became, de facto, a military body. Another set of regulations ensured that the Army (Sedena) and the Navy (Semar) could intervene in a practically unlimited manner in public safety as well as in various aspects of public life, without justification in all cases.

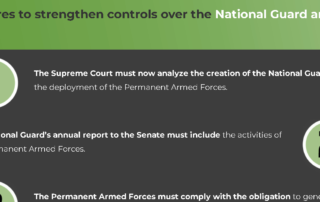

These provisions are clearly in violation of the Constitution and of binding international norms and judgments, and they give the military sector freedom to act with practically no civilian controls. As if this were not enough, an additional reform has been announced that will completely hand over the National Guard to Sedena and thus legalize what in fact is currently occurring.

Given this, various voices have highlighted the harmful impact that this unexpected deepening of militarization can cause from at least three perspectives: the possible increase in human rights violations, its ineffectiveness as a public policy to reduce violence, and the alteration of the delicate democratic balances in the civilian-military relationship.

For this reason, Centro Prodh has filed various claims. In the resolution of these the judiciary can act as a counterweight to guarantee respect for human rights. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court of Justice’s analysis of the National Law on the Use of Force and the attempt to resolve in Chambers –and not in Plenary session—the Constitutional Controversy over the contentious Presidential Decree through which the Permanent Armed Forces were made available for public security tasks, has raised concerns about the possibility of an inadequate scrutiny of these claims.

This issue of Focus tries to provide an overview to warn of the risks of militarization and to call for a return to create a civilian route. The experience of Centro Prodh leaves us not doubt the risks that an expansion of military leadership entails, risks which we extensively examine in our report “Military Power” (link in spanish).

Santiago Aguirre Espinosa

Director of Centro Prodh